“Fat”, “crazy”, “black” and “white” are disappearing from Western children’s books

Screenshot from YouTube

Viesturs Sprūde/Latvijas Avīze

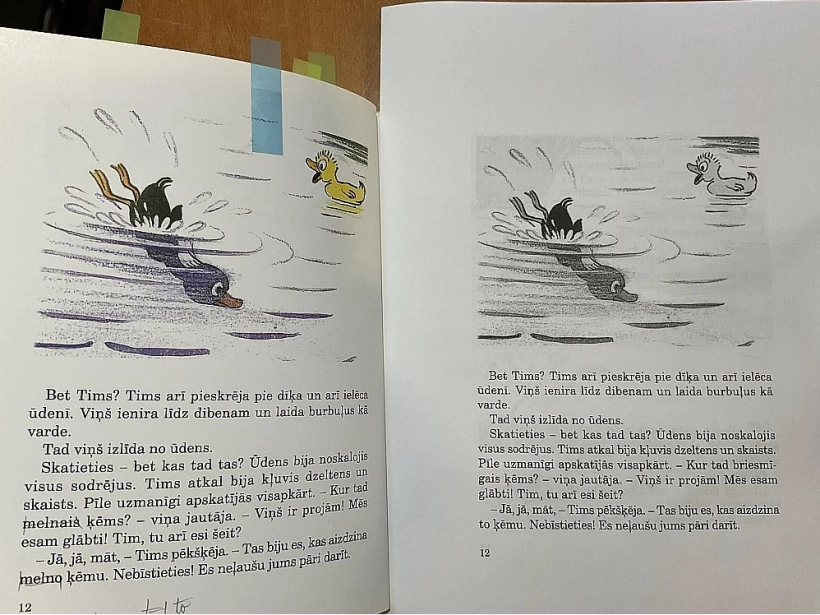

At the beginning of December last year, there was a great stir on the social media networks following the book and culture industries. The reason for this was a post on the Facebook page – Izcilas grāmatas – on 2 December by Vija Kilbloka, owner and chairwoman of the board of the book publisher Zvaigzne ABC. Specifically, that “finally, after several years of talking”, Hachette UK, the agency that owns the copyright to the works of English writer Enid Blyton (1897-1968), has allowed the printing of The Famous Jimmy in its original version, not the shortened Soviet-era version that has been translated from Russian.

However, the text will be “slightly edited”. For example, the text where Jimmy “crawled through a sooty pipe and turned completely black” has been corrected in the new edition to “crawled through a sooty pipe and turned completely dirty”, while the “black freak”, as he is called by his terrified duck siblings, has become more politically correct – “the scary freak”.

Photo from FaceBook

Meant as a happy announcement, the news triggered an explosion of negative emotions on social media networks, with calls of “Shame!” being sent in the direction of the publishers, asking rhetorically: “So, it has started here as well?” and suspicions that following an exaggerated political correctness may bring us more than one surprise in literature in the near future. When the number of comments on the post reached 250, the possibility of further commenting was closed. Later, in conversation, the owner of Zvaigzne ABC admitted that she would not have posted about Jimmy’s publication on social media networks if she had known that most of the public would misunderstand the situation, thinking that this was some kind of text revision movement coming from Latvia, whereas in this case it was a reality imposed by Enid Blyton’s copyright holders in the West, which publishers have to accept if they want to get a licence. “Besides, I could not even explain to you why Western society is the way it is. Everyone must see for themselves and come to their own conclusions,” Vija Kilbloka wrote in the Facebook dispute. To be fair, the post that sparked the outrage could indeed have been easily misunderstood.

Genders and colours

What are these processes, and will the “cancel” culture, which in this situation means censoring concepts that are considered politically incorrect, really take over all past literary works here too? The worldwide debate on the reception of literary works written in previous generations is not new. However, the growing cancel culture of literary classics is, by all accounts, only affecting certain cases.

In a way, it is probably a good thing if 70 years have passed since the author’s death and the legal successor is unclear, because then publishers may not seem to mind if someone wants to edit a text.

Only the author’s heirs, i.e. the right holders – usually the descendants of the writer and the legal agency that represents their interests or has acquired the copyright – can decide on changes to texts, not a publisher alone. It is acceptable for the publisher of an inconvenient or outdated term to provide a historical explanation and a reference to the time when the work was written.

Vija Kilbloka says that in Latvia, we mostly have to deal with situations where rights holders demand to see a translation. This was also the case with Jimmy: “Now we send translations of practically every book, especially children’s books, to the copyright holders for approval before we send them to the printers. Because it is in the contract. In the past, only the covers had to be sent. Now we print only when everything is approved.”

Photo from FaceBook

Sometimes reprimands can be difficult to understand. For example, why they dislike the translator’s use of diminutives. “All these genders, colours and skin colours… No one can keep track of it anymore. And that cannot be changed by showing some indignation. It can only change with a change of policy and a consensus that a book is a book. Sometimes it is funny, but for someone who lived through the Soviet-era censorship, it means nothing. And if we are now going to rewrite books in an easy-to-read language, how is that different from this?” says the publisher.

“They came for Dahl”

The most notable outburst yet from Western society over the political correction of texts by favourite authors came in early 2023, when the UK rights holders of Roald Dahl (1916–1990), the widely translated children’s and young adult author, the Roald Dahl Story Company and Puffin Books, part of the vast Penguin Books publishing house, also announced that they would “carefully” make hundreds of corrections to his works, making them “more suitable for a modern audience”.

In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Augustus Gloop was changed from “fat” to “huge”, and the oompa loompa, who were originally “little men”, were changed into gender-neutral “little people”.

In Dahl’s books, the words used to describe the characters were removed or changed – they were no longer “fat”, “crazy”, “ugly”, “flabby”, “African”, “Asian”, “black” or “white”. They could no longer be “dark red” or “white as a sheet”. The harsh principal Trunchbull in Matilda was changed from “most formidable female” to “most formidable woman”.

In several places, the author’s texts were supplemented with paragraphs that he did not write at all. Thus, in The Witches, which for Dahl are wig-wearing bald heads, it was stated: “There are many other reasons why women may wear wigs, and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.” The Mr. Centipede in James and the Giant Peach used to sing that “Aunt Spiker was as thin as a wire, and as dry as a bone, only drier”, but now this and other passages were replaced with descriptive, inexpressive footnotes.

The rights holders said the changes were made in consultation with “experts” from Inclusive Minds, a non-governmental think tank which says on its website that it is “a collective of people passionate about inclusion, diversity, equality and accessibility in children’s literature”.

Critics, however, have questioned the right of these consultants to revise, according to the times, the writing of other, much more talented authors and have raised the alarm.

As National Review, a US-based magazine focused on political, cultural and social events, put it: “First they came for Roald Dahl.”

The Puffin Books initiative was opposed with indignation by many prominent figures, including the then British Indian Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, and the Iranian writer Salman Rushdie. Several publishing houses in the US, France and the Netherlands said they would ignore the changes. The polemic over Dahl led a section of the literary public in the West to call for an end to “literary vandalism”, reminding us that great writers choose every word carefully. Offensive to some, perhaps, but splendid expressions are not an accident, but a way of creating the desired mood in a work. If the language is changed, the mood is lost and it is no longer THAT work.

And what if someone decides to repaint or correct scenes in artworks and musical compositions?

The result of the Dahl debate is that, at the moment, in the electronic world, books are “improved” automatically, while in the printed world both versions are available and Puffin Books has promised to publish the unedited Dahl in separate volumes. It should be noted that in early 2023, editorial changes were also announced for Ian Fleming’s James Bond series and for Enid Blyton’s The Famous Jimmy, mentioned at the beginning, as well as for other works of the author.

The “pure” Shakespeare

There have also been reminders that the trend has a history. In the early 19th century, the English physician Thomas Bowdler (1754–1825) revised William Shakespeare’s 16th–17th century plays to make the texts more “acceptable to families” and young people. This is when the term “bowdlerised” was born, as it came to refer to literary texts edited for political or social reasons. Thomas Bowdler published the stripped Shakespeare in a special collection which, by the way, was very popular and had five printings.

He did not only remove swearing and profanity from the texts, but also changed the details of the plot. For example, Ophelia in Hamlet drowned in an accident rather than drowned herself,and in Henry IV he completely removed the character of the prostitute, Doll Tearsheet.

Literary historians estimate that Thomas Bowdler shortened about 10% of the original texts. With the same good intentions, he rewrote the fundamental British historian Edward Gibbon’s multi-volume History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in the 1870s–80s and full of brutal scenes and descriptions of depravity.

Pippi and the “Negroes”

Astrid Lindgren’s (1907–2002) Pippi Longstocking was still racially and ethnically offensive in the mid-20th century. The work was first published in 1945, and it was not the above that first drew criticism, but rather Pippi’s anarchic freedom of thought and lack of respect for authority. For example, her resistance to the police. When the triumphal march of Pippi Longstocking began in the 1950s and 1960s, the text was immediately subjected to various corrections during translation, it was practically censored.

The French publisher Hachette wanted to transform Pippi from a “strange and spoiled child” into a young and lovely girl in the first translation.

Moreover, the French publishers believed that the young readers of their country would not believe in a little girl’s ability to lift a horse. The horse was replaced by a pony. The author objected, demanding that Hachette should then send her a photo of a French girl holding a pony. However, the French version of the book still went out to the public with a specific touch. According to literary scholars, this is the reason for the paradox that Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi quickly became a classic of children’s literature in other countries, while in France it went unnoticed. Only in 1995, the original version was finally printed in France. The discovery of the truth is said to have astonished French readers.

The first complaints about unwanted references to skin colour or nationality in children’s books, including Pippi, began ringing out in Western Europe in the 1970s. The situation became more serious in the 21st century, when German and British publishers expressed disgust that Pippi’s father was a “King of the Negroes” who “walks around all day with a golden crown on his head” on an island “full of Negroes”. Now he is “King of the South Sea”.

In Sweden, the change was long resisted, but it began in 2014 with the correction of texts and scenes for television films and shows aimed at a wider audience.

Not only was the “King of the Negroes” removed from the 1969 Pippi film, but also other details that could be linked to racial prejudice. For example, the moment when Pippi talks about the Chinese and slants her eyes while singing “Chinese”. The changes were agreed with the writer’s grandchildren, who felt that leaving things as they were might undermine the feminist message of “feminine power” in the book. The corrections provoked anger among most Swedes. This is probably why the Swedish editions of Pippi Longstocking in print have retained all the original elements, except for a note that “when describing people of African descent, the accepted expressions and terminology have changed over the years”.

In 2008, Latvia was hit by a stir in neighbouring

detective novel Ten Little Negroes under the new title And Then There Were None.

Estonia, where the local publishing house Varrak had published Agatha Christie’s (1890–1976) In 2007, the novel was reprinted in Latvia under the old title.

For Estonia, it was the first encounter with the new trends. The publishing house management had to justify that the title had to be changed at the request of the heirs of Agatha Christie’s literary contribution (it was denied that it was rather a demand). It should be pointed out here that the classic crime novel has long been known by both titles in the West. In the 1939 London edition it was Ten Little Negroes, but in 1985 the British changed the title to And Then There Were None – a title applied in the USA from the first 1940 edition, although some publishers in America also stuck to the original. Over time, in some cases, the word “Negroes” has been replaced by “Indians” or “soldiers” in the texts and in the title. Some critics have argued that this has been harmful to the author’s intentions,

since for Agatha Christie, the term “ten little negroes”, the title of a 19th century American theatre song, symbolises “the dark side of England”.

Imposed blandness

If Western publishers could resist the imposition of an edited Roald Dahl, perhaps Latvian publishers could also resist requests for dubious corrections to earlier works? Vija Kilbloka, owner of the publishing house Zvaigzne, reflects: “Well, if you have lawyers and the desire, you can do it. I have no intention of going to court. If the authors were still alive and able to defend their copyrights themselves, the agencies probably would not do that. But we have to work and The Famous Jimmy is a wonderful book, whether he is “dirty” or “black”.” Vija Kilbloka recalls the case of the Indian yoga specialist Sadhguru’s book Karma, when the person at the “other end” was on holiday at the time of the approval: “They did not reply, and we went to printing. Then they told us that they had contacted someone here in Latvia and that we had to correct the book here and there! And we cut the 2000 printed copies! And we corrected everything in the new one, although clearly in this case it was the agency’s fault. We could have argued, but it would not have mattered, because there was no justification there.

The question was: either you want to publish the book or not. If you want it, it has to be as the rights holder says, with whom it is written in the contract that you will do whatever is asked of you.

You can work with this agency, or not. That is it!”

As for Roald Dahl’s books, the ones currently in circulation in English were printed a long time ago, so they are still without political corrections: “The publishing rights are usually given for five years. If we renew the printing rights, there might be something new. But for now, we only have what was published before this new movement, before the overthrow of the Columbus monuments in America.”

Evija Veide also says that one of the most important things that a rights holder specifies in copyright contracts is that the translation must be of high quality and consistent in content and form. Resisting the copyright holder’s instructions would be an expensive step. Moreover, competition must be taken into account: “If publisher X says: “No, we want to keep the old version”, then there may be publisher Y who says: “We are modern and we think this is better. The rights holder will say: “You do not want it? Okay! We are happy to hand over this work to the Y.” There is not much hope for solidarity in the book business.

Provincial advantages

Evija Veide, Chairwoman of the Board of SIA Latvijas Grāmata and SIA Globuss A, who has been working in the book industry for 25 years, says that the publishing house Latvijas Mediji has never encountered such problems. Evija Veide adds that not only literary works are sensitive to political correctness, but also historical books, if they quote documents: “You cannot change anything there. This was the case, for example, in the books Viktora Arāja tiesas prāva published by Latvijas Mediji and Apsūdzības pret Viktoru Arāju un Latviešu drošības palīgpoliciju by Ričards Bērziņš. Someone was already worried, but if a particular testimony says “Jew”, it stays “Jew”, not “Hebrew”.

In fact, we would not have the right to change anything at all, because then we would have to change the whole Rūdolfs Blaumanis, but that would be too crazy.

By wanting to adjust everything to our own time’s view of things, we deprive this work of its belonging to a particular time, of its taste. If we make everything politically correct, it will really lead to blandness, it will change the writing, the style of the author, because this is not business literature, where only the bare information is important. It is also about form, manner and emotion. Maybe we just want to make the job of explaining easier for ourselves? Maybe we do need to explain to young readers why it says that? By making everything politically correct, we remove ourselves from this duty and steal from the author, the era and the work.”

Asked whether the Western cancel culture can be considered a tangible problem for the Latvian book industry, the Head of the Globuss chain says: “I think it is not a problem for us at the moment. But I cannot say whether it will not become a problem in a short time. Because it is evident that there is a major change in the way societies are perceived around the world.

Society is very drawn in and focused on different things that are becoming a distraction; looking at how to create a common space for different races and languages.

At both educational and cultural levels, various hybrids are inevitably emerging. In Latvia, it is not so wildly acute or actual at the moment. The role of the “province” benefits us there. But in the societies of large Western countries, where national composition, religious affiliation, language, experience, and traditions have changed, it could potentially be a catalyst for such things to become the order of the day. Literature inevitably remains as part of our spiritual heritage, but changes in society may force it to change as well.”