A Latvian citizen living in London claims the music of a world-famous producer as his own

Ilze Kalve, United Kingdom/Latvijas Avīze

In mid-January, the portal Cybernews.com published an article exposing the efforts of a 33-year-old Latvian citizen to steal the name and music of another artist and perform in London clubs. Cybernews investigates various cybercrimes, provides advice on information technology security and covers the latest news in the IT world.

Cybernews.com reveals the identity of the imposter

“Everything was copied and reposted, pretending it was all his. […] The only thing he did not repost was my photo because he did not know what I looked like,” says Karolis Labanauskas, a producer and composer from Lithuania, to Cybernews. Under the alias Embody, he has co-created world famous hits such as David Guetta, Galantis, and 5 Seconds of Summer – Lighter, which has just been at the top of the Latvian European hit radio chart for eight weeks.

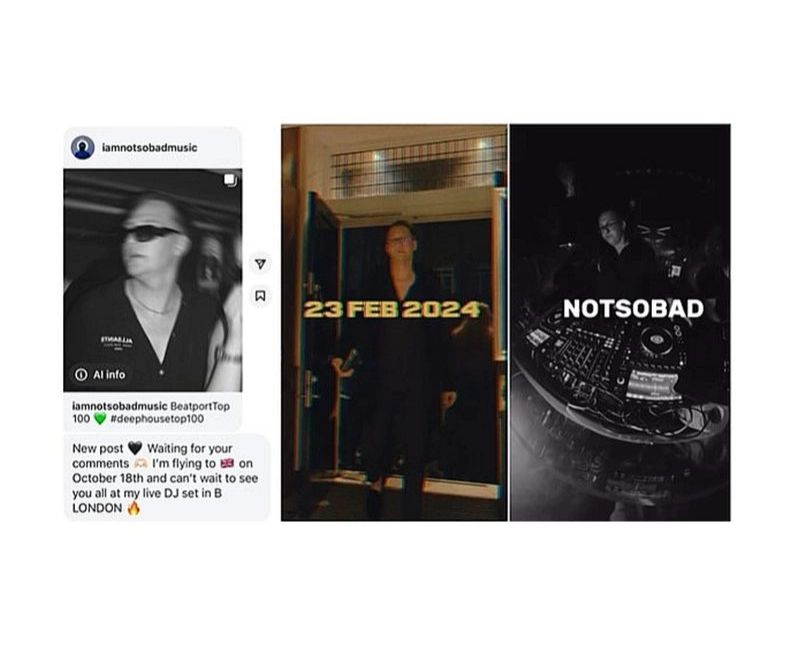

In addition to working with other artists, Karolis began a new project in 2021 under the alias Notsobad, which is a common practice among well known musicians as it allows them to experiment with different styles. Notsobad’s music became popular, quickly gaining new listeners, and soon a fake Facebook profile appeared, then other social media accounts.

The fake profiles were reported, but neither Instagram nor Facebook did anything.

Meanwhile, London-based event organiser and music producer DJ Mneemo, real name Yaroslav Gorovoy, was introduced to a Latvian, Ilya Grishkevich, who called himself DJ Notsobad, through mutual friends, saying that he had finally decided to start performing in public. The offer to play in a London club for free initially seemed very good, given Notsobad’s impressive online listener base, and promises were made to offer DJ Mneemo’s music to people in charge at well known record labels.

The situation would be the same if, for example, someone created a profile of Raimonds Pauls with his most popular songs, photos, descriptions, and this person came to the event hall claiming to be Raimonds Pauls and wanting to start performing regularly for no remuneration.

The impostor’s abilities are not convincing

Suspicions arose when hearing the music produced by Ilya Grishkevich himself, which was allegedly of a low quality and very different from the music of Notsobad published on the internet. Ilya Grishkevich also allegedly avoided being photographed for promotional materials, demanding that his photos be blurry or that he wear sunglasses. “His DJ skills were mediocre at best,” Yaroslav Gorovoy told Cybernews.

Suspicions grew even stronger in mid-October last year, when Ilya Grishkevich met with a possible business partner, Luke Power, at the B London nightclub.

When asked what he thought about using a granular synthesiser in one of his own tracks, Ilya Grishkevich could not answer and excused himself by saying that several people were involved in the making of the music, so he was not aware of the technical details.

Granular synthesis is a technique often used in modern electronic music to break down an audio into small pieces, which are then manipulated in different ways, for example by changing the speed or pitch of the sound.

The imposter was eventually caught when the real Notsobad contacted Luke Power. It should be noted that the person who impersonated Notsobad at the London club was Ilya Grishkevich, as the event organisers found out his real identity.

At the time, Cybernews began its investigation. Ilya Grishkevich was no longer reachable, he did not respond to e-mails and social media messages, and several of his accounts were no longer publicly available.

All attempts by Latvijas Avīze to contact Ilya Grishkevich, who lives in London, to find out his opinion were also unsuccessful.

What is the point of scam?

The real Notsobad, Karolis Labanauskas, says that the impostor not only stole his music, but also pretended to be him. “I think that he wanted to become a well known DJ,” Karolis Labanauskas tells Latvijas Avīze in an interview. “Nowadays, if you want to perform and travel, it is very important to create your own music. His own music did not give him that opportunity, because he lacked the necessary skills. So he came up with a plan – found a successful project, the creators of which were not publicly known, and pretended it was his, giving the impression that he was a successful DJ and music producer.”

The fake Instagram profile initially had even more followers than the real profile, with offers of collaboration and fan mail.

“Event organisers, who gave him the opportunity to perform, were surprised by his rude behaviour and poor quality performance, which in turn jeopardised the reputation of the event,”

Karolis Labanauskas explains. “The industry is not that big, everything is based on trust, so information spreads very quickly and the nature of the artist is one of the determining factors in whether someone will work with you or not,” says the experienced music producer, who believes that his own reputation was damaged as a result.

As it was not possible to delete the fake social network accounts, Karolis Labanauskas had to investigate and warn everyone who could be warned. The incident has also been reported to the police in Lithuania.

The other victim of the scam, Yaroslav Gorovoy, who knows the situation in London clubs well, explains that it is common practice for unknown DJs to perform in London clubs for free to gain popularity. Only well-known DJs who also have many followers on social networks get paid royalties, as this ensures good attendance and profits for the club.

“When Ilya Grishkevich contacted us, he said it was his first public appearance, presenting himself as someone who wanted to start a DJ career in addition to his creative work in a recording studio,” the event organiser tells Latvijas Avīze. “We feared taking a risk, so we offered him to play at the very end – the last hour of the night, which is usually less critical for the overall success of the event.”

This case has been a good lesson for everyone to be extra cautious in the future.

Fake contacts with local celebrities

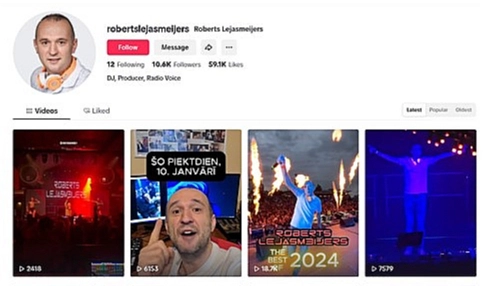

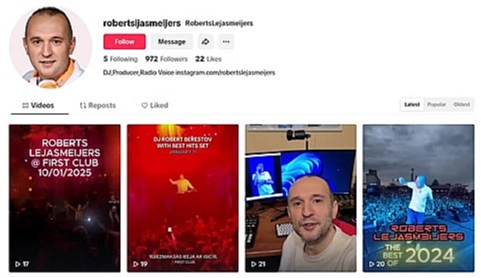

Faking accounts of Latvian celebrities has become almost a daily practice. For example, Roberts Lejasmeijers, who is known as both a DJ and a music producer, has also had several fake accounts. “There are two on TikTok, one of them even messages others. They took my picture, my name – Roberts Lejasmeijers, they pasted all my videos. If I saw it myself, I would believe it was my account! Only my username is Roberts Lejasmeijers, but the fake profile is Roberts Ljasmeijers, missing the letter “e”, which is hard to notice.”

The followers on the real account are growing rapidly on TikTok, where the experienced DJ also posts videos of his live performances.

Roberts Lejasmeijers says: “I specifically tell my followers to “play” along with the fake profile to see how far it goes. So far it has taken us to a WhatsApp account, registered to a number in the Philippines, and also to a Telegram account. Probably after a while the imposter will say – times are tough now, have a show tomorrow, can you transfer some money? Or they are stuck somewhere at the airport and need money. Maybe someone would transfer it, because they might think – Roberts Lejasmeijers is a well known DJ in Latvia, maybe he really has problems, he will pay back!” He adds that this is the first time he has ever encountered something like this: “I thought only big famous influencers faced this!”

OPINION

Imposters are not just after fame

Vitālijs Rakstiņš, Head of the National Defence Service Department at the Ministry of Defence, a security expert with many years of experience: “The risks associated with creating fake profiles of well known people are most often related to reputational and fraud risks. For example, one of the first high-profile incidents occurred in 2012, when fraudsters created a fake social network profile of Admiral James Stavridis, NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe. No NATO officials were found to have disclosed any sensitive information to the fake admiral, but the risks of espionage, including economic or corporate espionage, certainly exist. Three years ago, a case in which the identity of Latvia’s then Minister of Defence, Artis Pabriks, was used to scam a large sum of money from a woman in the United Kingdom received widespread media attention.

Followers of celebrity profiles are exposed to the risks of fraud, misinformation or deception if the fake idol spreads false news or engages in phishing.

Many platforms have identity markers, but they cannot always be trusted. It is best to check the date of creation of the social network profile, the pictures, the description, the number of followers, paying attention to the content posted. If in doubt, it is best to look for social network accounts on the official websites of officials or celebrities. Unfortunately, nowadays even popular people who have never had a social network account have to regularly check and monitor the web to see if someone has made a fake account in their name.”

REFERENCE

What does the copyright law say?

Copyright laws around the world state that copyright is valid from the moment a work is created, but with the development of technology, various forms of fraud are also spreading.

Authors themselves must protect their works carefully, for example by publishing works on the internet and using various technical markings and identification tools to prove authorship in the event of a dispute.

It is advised to keep records of where and when works have been published, and to evaluate websites and their reputation.

Target sites should be regularly analysed and, if an infringement is identified, site administrators should be asked to restrict illegal content.

Accounts on social networks have to be linked to the identity of individuals, otherwise the works posted on the account do not belong to the individual, but to a virtual, unidentified sequence of symbols without legal capacity.

If an infringement is found, the author or a representative of rights must document the facts of authorship and make a specific request to the publisher, for example to stop the illegal publication of the work to the public or to obtain a licence to use it. If this is not possible, the editor of the website should be contacted and asked to stop the illegal publication of the work. If the request is not responded to, the website provider should be contacted.

In practice, this means that an e-mail is forwarded to each subsequent addressee with the authorship summary and, if authorship is substantiated, the author of the work is likely to be compensated by the infringer or the illegal publication of the work is stopped.

If the illegal publication of the work to the public is not stopped, the author should apply to the Consumer Rights Protection Centre for action against the intermediary service provider who has failed to comply with its obligations under the Digital Services Act and to stop the illegal publication of the work to the public.

If the dispute is still unresolved, the person can file a complaint with the State Police or the courts. When filing an application with the State Police, the author must, in addition to proving authorship, substantiate the amount of the damage to its rights, which must be at least ten minimum monthly salaries.

Source: State Police