Ivars Bušmanis, ‘Latvijas Avīze’, Vojtěch Berger, HlidaciPes.org

Member of the European Parliament Dace Melbārde, seeking support for Latvia’s weakened local press in the border regions, initiated a European media policy and came across unexpected findings about news deserts in the heart of Europe.

Deserts of Latvia

We pass by Skļarovščina, Koškovci, Gorbačovi – in the far corner of Latvia, in Piedruja Municipality. On the other side of the Daugava – Belarus. Houses are either abandoned or the owners are not at home. But almost all TV decimetre antennas are pointing across the border – towards Belarus. In Dvorčani, we spot one house on the bank of the Daugava without an antenna. A car has just pulled into the homestead and the owner of Lingaži gets out. “No, we have neither TV nor radio. My husband tried this and that, the technicians came, but nothing worked. We only have the internet – I follow delfi.rus, gorod.lv, I get local news from Ezerzeme in Russian and the municipal newsletter Krāslavas vēstis,” says Jeļena.

Jeļena, the owner of Lingaži, does not have access to Latvian television and radio near the border with Belarus, but gets her local news from the regional newspaper Ezerzeme in Russian.

Anita Biseniece, who lives in Vecpokaiņi in Naudīte Rural Territory, Dobele Municipality, has not had a TV for 12 years, and she herself gave up on it. “I cannot make calls with Tele-2 because there is no signal. I only have an antenna on the roof to get the Internet.” Our conversation is also via the Internet telephony. “What I find interesting, I watch what is available free of charge on the Internet, but I watch TV programmes about the environment on the lsm.lv website. The postman only brings home crossword puzzle magazines.” Anita is so upset about the closure of the Dobele Municipality newspaper Zemgale that she wants to take part in the creation of a new newspaper. “The newspaper closed because there was not enough local news. It published a lot of things that could be read elsewhere. It needed to provide more solutions to the various pressing issues.”

Two different examples. One corner of Latvia that is not covered by radio and TV tower signals. The other – a municipality covered by communications and media outlets. Which one is in the news desert? When mapping Europe’s news deserts, a paradox emerged – Dobele Municipality is a bigger news desert than Krāslava Municipality. And Riga – even bigger. But in the Czech Republic – even bigger. Why?

A desert in Riga and around

Since Rīgas Balss ceased to be published, the capital has no independent newspaper to monitor and evaluate the work of the municipality. “The capital Riga and the surrounding municipalities do not have either one local or regional media. For this reason, Riga and its surrounding municipalities are identified as news deserts in this study. These areas are not lagging behind economically, nor do they suffer from low Internet penetration,” is the conclusion about Latvia in the News deserts in the European study by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom at the European University Institute.

Rīgas Apriņķa Avīze, which is addressed to the Pierīga Municipality audience, is also not an independent media, as it is still co-owned by several municipalities, explains Ivonna Plaude, head of the Latvian Regional Media Association, to Latvijas Avīze. Latgales Laiks was one of them, but now it has been free from the presence of the Daugavpils Municipality in its ownership for more than a year, she adds.

Three local newspapers have disappeared in the last five years – in 2019, Alūksnes Ziņas and Malienas Ziņas merged, and a year later Kursas Laiks ceased publication in Liepāja (continues publications on Rekurzeme.lv). But this is not a major risk, as local journalism exists in these regions. However, the closure of the newspaper Zemgale in Dobele due to insufficient readership numbers is already turning the region into a desert. With 8000 printed copies, it cannot replace the municipality’s Dobeles novada vēstis, because it lacks a media that evaluates the municipality.

Where they exist, 55% of people trust local news, according to a 2022 Kantar survey. There are currently 33 local newspapers in the country, plus regional radio and TV studios. However, be aware that only 36% of the population has read a local newspaper in the last month. Ivonna Plaude concludes that the number of local journalists continues to decrease steadily. Lack of editorial staff, lack of funding, ageing newspaper premises, difficulties in attracting young journalists, low salaries, overworking are the specific features of the Latvian local media scene. Late mail deliveries also lead to a decline in the number of subscribers.

“The study underlines the urgent need for new solutions to support local and regional media, especially in the area of digital transformation, in addition to permanent institutional support. If we do not start thinking about this today, we risk the disappearance of local journalism and the emergence of vast news deserts in Europe,” says the study’s initiator, MEP Dace Melbārde (now Vienotība, Group of the People’s Party).

The first power supports its critics

When I interviewed Dace Melbārde two years ago, she had already become one of the most influential media policy-makers in the EU. She was the one who called for 2% of the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility to be allocated to the cultural, creative and media sectors. She called for a permanent fund to support media and journalism – but this failed because the funding facility was moved under the Creative Europe programme for culture. “This does not give the right impression of the media, as if they work within culture. We need to look at media as a separate sector that needs a separate financial instrument,” says Melbārde.

“New solutions to support local and regional media are urgently needed, in addition to permanent institutional support,” said MEP Dace Melbārde at the presentation of the study in Brussels on 5 March.

After her election to the European Parliament’s Committee on Culture and Education, she became the coordinator responsible for the agenda. “There was a complete void of ideas on whether and what to do with the media. Because there was no clear media policy at the EU level, only support for the production and distribution of films for the audiovisual media. I had fresh experience because during the Latvian Presidency of the EU, as Minister of Culture, I highlighted several media issues,” recalls Dace Melbārde. She prepared a report with solutions to strengthen Europe’s media environment. This led to the adoption by the EP in 2021 of the Resolution on Europe’s Media in the Digital Decade: an Action Plan to Support Recovery and Transformation. She managed to trigger support mechanisms for journalism.

There have now been several competitions in the MEDIA strand of Creative Europe, in which Latvian media have also participated. Dace Melbārde’s actions are proof that one MEP can achieve a lot, even in a previously unregulated and regulation-sensitive environment like journalism.

Two years later, we meet in Brussels at the European Parliament, where a study on news deserts concluded on 5 March.

The desert map is ready

The study Uncovering news deserts in Europe: Risks and Opportunities for Local and Community Media in the EU maps local and regional media to show where news deserts, or places where there are no longer professional local media, have already developed or are at high risk of developing. The Centre for Media Pluralism and Freedom (EUI-CMPF) involved researchers in all Member States.

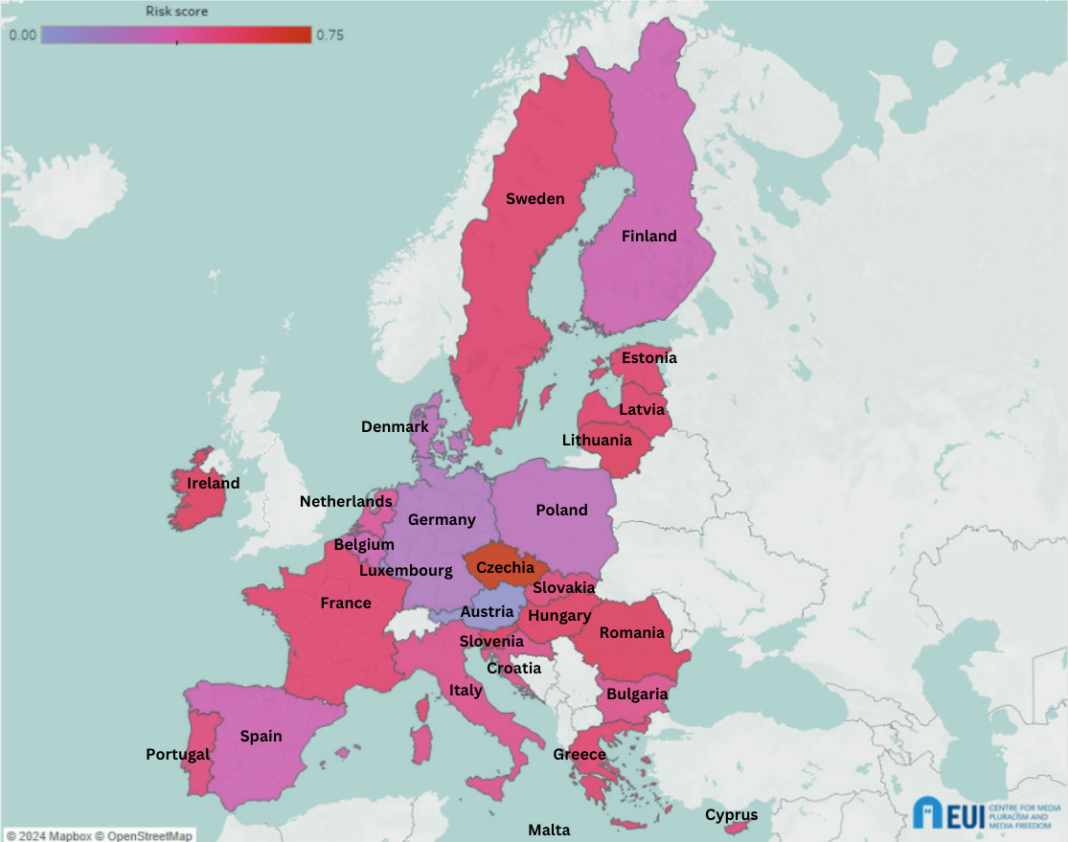

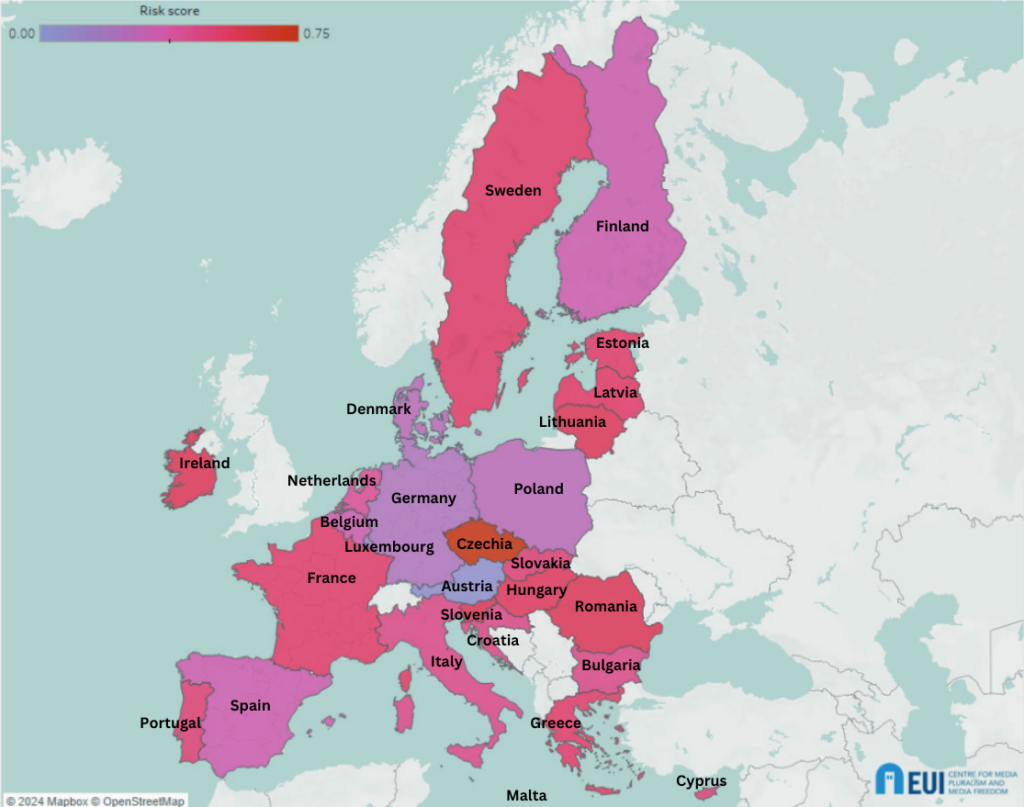

The researchers assessed the risks based on 55 variables, grouped into six indicators: the existence of local media and journalists, market conditions, journalists’ safety and working conditions, editorial independence, social inclusiveness and examples of good practice. The Czech Republic has the highest risk of local media infrastructure (75%), while the Baltic countries have around 55%. The greatest risk is posed by declining advertising revenues, which are rated as very high in six Member States, including Latvia. But overall, the market is again most unfavourable in the Czech Republic (94%).

The financial gap is linked to the ageing of the printed press audience and the consequent decline in subscribers, as well as the audience’s reluctance to pay for news online. As a result, the number of local journalists has declined across Europe.

Local media in the EU also face unfair distribution of public advertising and subsidies. Most media in Central and Southern European Member States experience political control.

Giovanni Melogli, President of the EUI-CMPF European Media Initiative, points to the threat to journalism in the “post-truth” era: “Active and pragmatic local newspapers and local journalists are essential to brining the emotional part of information down to its rational logical foundations. Because local media cover specific aspects of everyday life that are verifiable and understandable to citizens. The second important element: we see journalism as a watchdog of society against political and economic power, but we would like to highlight another important element: the mediating role of journalists. Good journalism must be able to bring together and reconcile different interests.”

“It is good that we highlighted the emergence of news deserts as a phenomenon. This study shows very clearly that this phenomenon is not only relevant for Latvia, but also for the whole European Union. News deserts are a huge threat to one of the European Union’s most fundamental values – democracy,” concludes Dace Melbārde in a conversation with Latvijas Avīze. Until now, I was convinced that the biggest desert would be in Latvia – especially along the borders with Belarus and Russia. But look, the Czech Republic surprised us by being even worse, because there are practically no local media.

Risk level of local media infrastructure in the 27 EU Member States

Source: The Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (EUI-CMPF)

The highest risk is in the Czech Republic, where there are no local newspapers. In five countries – Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Slovenia and Slovakia – the risk remains high because, although there are some outlets, they do not reach the population in the outermost regions. Latvia is assessed as medium risk.

Regional media are disappearing in the Czech Republic

In the Czech Republic, there has long been talk of the extinction of local media, which is known as the emergence of news deserts. The latest research shows that the prospects for local journalism in the Czech Republic are comparable to Orbán’s Hungary. The Czech Republic scores poorly even compared to the much smaller Latvia, where the state, at least partially, supports the media.

In the Reporters Without Borders study, Latvia, 16th place, and the Czech Republic, 14th place, are separated only by two places in the media freedom rankings. The gap between regional and local media is much deeper – worse for the Czech Republic.

In the Czech Republic, unlike Latvia, the state does not support the media sector in any way, either through a system of direct financial support or indirectly through a reduced tax rate. On the contrary, the government has increased VAT on newspapers and magazines from 10% to 12% as of this year. However, this was only after the planned 21% rate was challenged by the media and the public.

In Latvia, the support of the Media Aid Fund, which gives 10 to 20% of funding to local newspapers, the restrictions on local government newsletters, the reduced 5% VAT on the press, and the reimbursement of postage costs for newspaper deliveries keep local journalism afloat.

“I am surprised about the Czech Republic. But I am not surprised about Latvia’s medium risk rating. If seven or eight years ago we had not started to develop a national media policy, who knows what the situation would be like in Latvia… We managed to establish a number of things that allowed local media to stay afloat. But we should not lull ourselves into thinking that things are worse elsewhere, because we are in a completely different geopolitical situation, we have a different social structure, also compared to the Czech Republic,” says Dace Melbārde, Latvia’s representative in the European Parliament.

Worse than bark beetles in the forest

The European media map colours countries from blue to red according to six indicators. The Czech Republic is most often shown in dark red, indicating a serious problem. The level of these risks in the Czech Republic is rated as high to very high, in Latvia only medium to low.

Three years ago, journalist Tomáš Trumpeš from the Czech local newspaper Ohlasy dnevne na Boskovickku compared the situation of regional and local media in the Czech Republic to a forest ravaged by a bark beetle. While new plantings are already growing in Czech forests, the country’s news deserts are expanding.

The authors describe the “sandwich economic pressure” under which small regional and local editorial offices in the Czech Republic are coming under. On the one hand, they face competition from dozens of regional versions of the daily Vltava Labe Media newspaper and, on the other, from local newspapers. In order to retain at least some advertisers, local media prefer to refrain from publishing some critical texts that could put local businesses against them. The financial weakness of these media then also means that they are weak to defend themselves against attacks from local or regional politicians.

The study refers to testimonies of regional journalists that they cannot report on certain topics because of their media advertising interests. Regional journalists are also weakened by the fact that many of them work as freelancers without job security and social benefits.

The number of local newspapers in the Czech Republic has decreased by half over the last decade, and the remaining ones are losing diversity. For example, the aforementioned Vltava Labe Media newspaper Deníky last year merged the front page design of some of its regional editions – and reduced the number of original cover pages devoted to local issues from 70 to 28.

Quasi-media of local politicians

There are many examples of local or regional media getting too close to politicians. For example, in 2023, the Council for Radio and Television Broadcasting fined the Liberec television station RTV+ 50 000 Czech crowns (EUR 1979) for producing a news and journalism programme for the Liberec region under a contract that allowed the client to influence the content, and approve the format of the programme before it was broadcast.

There are also examples where the owner is a politician. For example, in Plzeň, ZAK TV, and its associated website Plzen.cz are run by Radek Novak, a politician from the Civic Democratic Party ODS. Although Plzen.cz describes itself as a “news portal”, Radek Novak, for example, writes comments there without mentioning that he owns the website. According to the analysis, ZAK TV is “substantially financed by contracts with public institutions”.

Another example are the websites Chomutovky.cz and Karlovarky.cz. They are published by a company owned by Jirkov City Councillor Patrik Macák. Thanks to his connections and business contacts with the local leader of the PRO party, Matěj Drbohlav, texts and interviews with faces of the party appear on the websites with striking frequency, without any mention of proprietary links.

Orbanisation without Orbán

A study by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom in Europe cites at least a few positive examples, mainly online media, which respect journalistic standards even under such pressure. For example, the Drbna.cz regional network of websites or the Ohlasy.info website mentioned above. The Ostrava-based Okraj editorial office is also new this year.

Newly published data shows that so-called news deserts are not a single country problem, but a European problem. However, the Czech Republic has gone dangerously far in expanding them compared to other countries. This is not only evident from a comparison with Latvia, but also from a look at Hungary, the Czech Republic’s closest neighbour.

According to the survey statistics, regional journalism in the Czech Republic is in an even worse state than journalism in Hungary. Hungary is ranked 72nd in the Reporters Without Borders press freedom ranking. The reasons are well known: the nationalisation of the public media, long-standing restrictions on journalists and economic control of the media and advertising market.

Hungary’s domestic media scene is very diverse compared to the Czech Republic, with district newspapers, dozens of regional TV and radio stations. The problem is that most of them are part of the state media conglomerate KESMA and thus under government influence. This results in the distribution of content that accommodates the government rather than criticises it. Orbán has also been distorting the state media market for years by distributing state advertising unequally. Media that are critical of the government are hardly given any public money at all.

So, while the Czech media often warn about the “Hungarian way” and “cleaning up the media”, the fact is that the Czech Republic arrived at the news deserts in the regions in exactly the same way – even without Viktor Orbán.

Rain in the news desert

As part of the News deserts in Europe study, the European Federation of Journalists is piloting “Local Media for Democracy”, which supports 42 local and regional media projects with EUR 1.2 million of EU funding, two of them from Latvia, mostly for Russian-language news. One is the EUR 35 260 Daugavpils portal chayka.lv (published by DAMedia), which is committed to providing different content to the Russian-speaking audience in Latgale and Latvia.

The other one is in Jelgava – for the portals jelgavniekam.lv (closed this week) and novaja.lv in Russian, both published by SIA JK Media Group, owned by Jurijs Karlinskis. Inga Karlinska, the project manager, explains that the project will cost EUR 40 000 to improve both portals, which will be available in a new, modernised look in June.

But these two pilot projects are a temporary financial windfall. The situation is similar in Belgium. “I work for the Antwerp, Belgium-based web platform apache.be, which targets a Flemish-speaking audience. We are six full-time journalists, but we still have 20 to 25 freelancers writing for us,” one of the full-time journalists, Steven Van Den Busse, told me in Brussels.

“For this project, we were looking for journalists who could write a good investigative piece from a small town or community. We started with one municipality and spent several weeks researching what issues would be important to the people there, but which were not publicly talked about. We intend to write two or three such stories. In this project, we will highlight this local issue on our portal, and we will publish a newsletter for the community we are writing about.” The Flemish journalist told me that this is a one-off action – just for this project. When the project ends, so will the increased interest in local life. It will be worth it if we can attract a local journalist for a longer-term cooperation, Steven hopes.

Thus, such projects are like rain in a news desert. Once it rains, everything turns green… and then dries out again until the next EU financial aid shower. But how can local journalism create permanent oases?

How to turn deserts into growing field

While there is no such thing as an instant way to irrigate the news desert, the study explores some new strategies for engaging audiences, such as e-mail newsletters, podcasts and “slow” journalism, or in-depth research and audience engagement.

State and local authorities should support innovative media libraries or directories and innovation in local media (technological developments, new business models, diversification of news formats).

Publishers should invest in innovative practices and technologies that attract audiences in the long term while being able to adapt to changing audience preferences and behaviour.

Media should build networks. Journalists should try new storytelling techniques, formats, artificial intelligence and platforms.

Shutterstock photo ID: 1549786853

Surprisingly, the Czech Republic is the biggest news desert in the EU due to threats to the infrastructure of local newspapers, political interference in content.

REFERENCE

What is a news desert?

• The term “news desert” was created in the US to describe the effects of the crisis in traditional media and the decline of regional and local media after the 2008 financial crisis.

• A rural or urban community with limited access to sufficient, reliable and comprehensive news sources.

• No local news distribution channel that remains independent from those it reports on and targets in a given geographical area.

• Such news is a necessary condition for a functioning democracy at grass-roots level.