International law prohibits arbitrary detention and taking civilians hostage during armed conflict. The forced displacement of populations by an occupying power is considered at least a war crime. However, Russia has systematically violated international law since 2014, and in the two years since the full-scale invasion, it has only increased the scale and brutality of its treatment of Ukrainians. Thousands of civilians have been captured and taken from their homes, being held in inhumane conditions without any legal grounds for their detention.

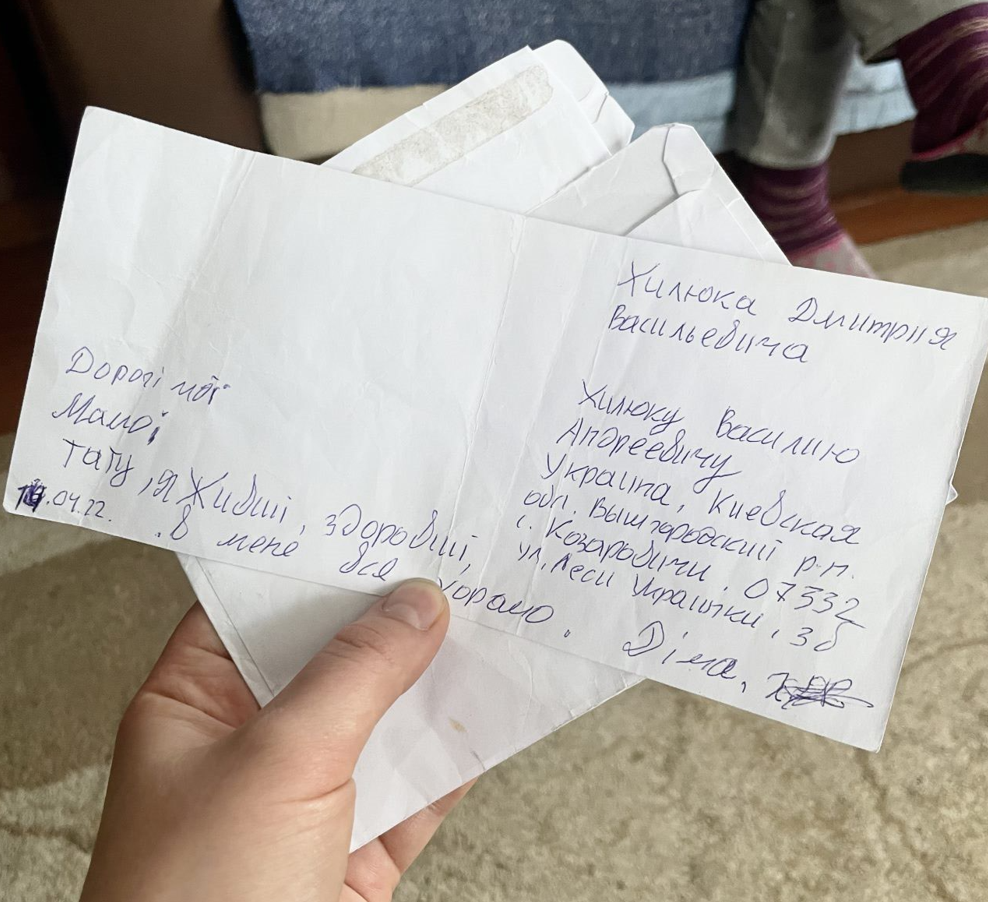

“Dear Mom and Dad, I am alive and well, everything is good with me. Dima. 14.04.22,” — Halyna Khilyuk holds a small piece of paper with a few words written in an unsteady hand. She is over 70 and has difficulty moving due to the aftereffects of a stroke. This scrap of paper is the only news she has received about her son Dmytro in over two years. He was kidnapped by the Russians from their home in March 2022, taken to Russia, and has been held in prison there ever since.

Before the full-scale invasion, Dmytro Khilyuk worked as a correspondent for the Ukrainian news agency UNIAN, covering law enforcement and court activities. He lived with his parents in the village of Kozarovychi, 25 kilometers from Kyiv. The Russian troops occupied the village on the third day — February 26, 2022. They immediately began occupying people’s homes, digging trenches in their yards, setting up checkpoints, and detaining civilians.

On March 1, the Russians came to the Khilyuks’ house for a search, but no one was detained. On the evening of March 2, a Grad missile hit their house. The family survived, but the wall, roof, and windows were damaged, so they decided to move to a neighbor’s house. On the morning of March 3, Dmytro and his father Vasyl went to check the damage to their house but were unable to enter the yard. Five Russian soldiers held them at gunpoint in the garden. They were searched, shots were fired near their ears, jackets were thrown over their heads, and they were taken to a place where all detainees were held.

Initially, Dmytro and Vasyl Khilyuk, along with other villagers, were held in Kozarovychi in warehouse facilities for five days. On March 8, they were taken to Dymer, the central village of the community, to a local enterprise’s premises. It turned out that detained men from the surrounding occupied villages were brought there. They were kept in cold and dirty conditions, without light or water, and were constantly taken for interrogations. Initially, Dmytro said he was a teacher, but eventually, he admitted that he was a journalist.

On March 11, Dmytro was taken from Dymer to an unknown location and has not been seen by his family since. Vasyl and nine other men were released the same day. When Vasyl asked when his son would be released, a Russian soldier replied, “He will return soon, when the war is over.” Vasyl walked back to Kozarovychi, but he could not enter his house — it had been occupied by the Russians.

Kozarovychi was de-occupied on March 31, when the Russians left the village in an organized column overnight. Ukrainian investigators soon arrived, recorded Vasyl’s testimony about his son’s detention and captivity, and opened a criminal case against the Russians, but there was little else they could do. In April 2022, Russia confirmed that it was holding Khilyuk, but his location, the charges against him, and his condition were unknown. Until August 2022, the parents knew nothing about Dmytro’s fate until they received this note on a scrap of paper stamped with “Russian Post.”

Dmytro Khilyuk’s story is one of thousands like it. The National Information Bureau on Prisoners of War, Forcibly Deported, and Missing Persons currently lists 14,045 missing civilians. Among them are 1,745 confirmed victims of enforced disappearances and unlawful detentions by the Russians, 919 of whom have been tracked with the help of the International Committee of the Red Cross. There is no information about the whereabouts or condition of thousands of other missing Ukrainian civilians.

There are currently over a hundred known places where Ukrainian civilian hostages and prisoners of war are held in Russia, Belarus, and occupied territories of Ukraine. The Ukrainian Media Initiative for Human Rights has presented an interactive map of these locations. Released captives testify about torture and abuse by the Russians. They report being held in unsanitary conditions, without enough food, drinking water, or medical care, and being subjected to mockery, intimidation, and insults, regardless of age, gender, or health condition.

“The situation with civilians is much worse than with prisoners of war. Primarily because the Russians themselves do not want to acknowledge the existence of Ukrainian civilian prisoners, as they simply do not have the right to hold them, according to the Geneva Conventions,” explains Oleksandr Kononenko, a representative of the Ombudsman’s office in the security and defense sector. Consequently, exchanges involving civilians are impossible, as it is unclear who or what they would be exchanged for. Additionally, such a move by the Ukrainian authorities could provoke the Russians to take even more civilians from the occupied territories hostage.

Therefore, the only solution for Ukraine at the moment is to exert international political pressure on Russia to release all civilian citizens unconditionally. Ukraine is actively working in this direction. In February, the first meeting of the International Platform for the Release of Illegally Detained Civilians by Russia was held, joined by over 50 countries and international organizations. Norway and Canada became co-chairs of this platform. Additionally, Ukraine is actively negotiating with potential “protecting power” that could mediate between Ukraine and Russia. “Qatar has expressed interest in becoming a mediator on this issue. But this requires the consent of both countries — Ukraine and Russia,” Kononenko adds.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s primary task is to identify, locate and establish contact with as many civilian hostages as possible, whom Russia is holding and hiding from the world. Law enforcement officers and human rights defenders are painstakingly gathering such information by interviewing released prisoners of war and civilian hostages and monitoring Russian propaganda media and social networks. Thus, Halyna and Vasyl have received several confirmations over the past two years that their son Dmytro Khilyuk is alive — freed soldiers heard his name in the detention centers and colonies where they were held by the Russians, and some even saw Dmytro in person.

The latest news about him came with the most recent exchange of prisoners of war on May 31, 2024. One of them reported that he had shared a cell with the journalist for almost 11 months: “He sends his best regards to his parents and brother. He says he is alive and hopes to be released.”