Discussion at the University of Cambridge sees an end to the current world order

Photo: Shutterstock

Ilze Kalve/Latvijas Avīze

In early January, the newly elected US President, Donald Trump, shocked the international community and infuriated the Danish Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen, by announcing that the US wants to take control of Greenland, which is an autonomous Danish territory.

The Prime Minister of Greenland, Múte Egede, also did not remain silent: “We are not for sale, and will never be for sale.” But why has Donald Trump suddenly started talking about a territory belonging to another country, why would anyone be interested in an island beyond the Arctic Circle, what do the Danes think about it and, after all, what do the Greenlanders themselves think about it?

The green land that is not green

Greenland is not green at all, as 85% of the land is covered by ice. It was named the Greenland at the end of the 10th century by the Viking Erik the Red, who was sent there as a punishment in the hope of attracting other Vikings to settle there.

Scientists say that Greenland, the largest island in the world at 2.16 million square kilometres, was indeed green more than 2.5 million years ago. Today, there are 56 700 residents (2024 data), 16 000 of whom live in the capital, Nuuk; 88% of them are Inuit, Greenland’s indigenous people, who do not like to be called Eskimos.

Greenland, which is similar in size to Mexico and France combined, and in population to Jelgava, is the least populated place on Earth, with no roads or mobile phone coverage outside the populated areas.

Historical affiliation

Over the centuries, Greenland has belonged to Denmark and Norway. In 1933, the International Court of Justice in The Hague declared that Denmark had full rights to Greenland. In 1940, an agreement was made with the US government to use Greenland for military operations. In 1941, the US occupied Greenland and established a US Air Force base there in 1943, and after the end of the war offered Denmark USD 100 million for the territory, but the offer was rejected.

In 1953, Greenland was constitutionally declared part of Denmark, with the right to self-government and its own members in the Danish Parliament.

In 1982, the Greenlanders voted by a 53% majority to leave the European Economic Community, which they had to join with Denmark in 1973. Since 2009, Greenland has full control over its natural resource extraction and partly over its foreign affairs.

The debate on full separation from Denmark has been reignited with fresh vigour, with 84% of survey respondents voting in favour of independence.

However, full independence from Denmark would pose very serious economic and security challenges, as the island is dependent on Danish subsidies of around EUR 500 million per year.

Greenland has abundant mineral resources for the production of electronics, batteries, wind turbines and military equipment, as well as gold, diamonds, platinum and palladium, uranium, oil, gas, etc. Climate change is likely to open up new maritime routes in the Arctic, further increasing Greenland’s strategic importance and making it of particular interest not only to the US, but also to China and Russia.

Back in 2019, Donald Trump already expressed interest in acquiring Greenland, but Denmark rejected it. Six years later, Donald Trump is once again talking about it, even threatening to use force.

One NATO member against another?

To better understand the situation in Greenland, the Centre for Geopolitics at the University of Cambridge, together with the Scott Polar Research Institute, organised a discussion in February on The Geopolitics of Greenland: Past, Present, and Future, where experts from several countries shared their perspectives.

Greenland has been considered a valuable asset for decades because of its military importance and natural resources.

During the Cold War, Greenland played a key role in US military strategy, enabling the stationing of major military bases there, including the Thule Air Base, which has now become a key component of the US Ballistic Missile Early Warning System.

The discussion raised concerns about Donald Trump’s unpredictable foreign policy, but noted that the US interest in Greenland goes beyond the Donald Trump presidency and is a long-term strategic priority. As Greenland has no army of its own, cooperation with NATO is an important part of its security strategy. Experts suggest that Greenland could establish a coast guard in the future.

There is no such thing as a better coloniser

The relationship between Greenlanders and Danes is complicated because Greenlanders themselves see the Danes as colonisers. Sara Olsvig, International Chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council and former Member of Parliament, points out that there is no such thing as a “better coloniser”: “The governments [of Denmark and Greenland] have agreed to work together to assess the consequences of colonisation. Not only the consequences until 1953, which is the end of the formal colonisation era,

but also what happened after that when specific programmes, specifically colonial programmes, led to systematic discrimination against Inuit and Greenlanders, both in Greenland and in Denmark.”

Sara Olsvig has been Minister of Social Affairs, Families, Gender Equality and Justice in the Government of Greenland, so she has a lot to say about discrimination. In the 1960s and 1970s, a birth control programme was introduced with the approval of the Danish government, when half of women and girls of childbearing age were given intrauterine devices. The devices were often inserted without the women’s knowledge or, if the girls were minors, without their parents’ permission. This is why a group of 143 Inuit women took legal action against Denmark last March. “It is clear that this was a deliberate policy of the Danish government after the end of the formal colonial era,” Sara Olsvig concludes.

The fact that Greenlanders still consider Danes as colonists is confirmed by the panellist, the Norwegian student Lewis Andre Koshnas, a student of Modern European History at the University of Cambridge, who himself worked in Greenland for a short period of time: “When we talk about Greenlanders, we usually mean Inuit, but most Greenlanders are a mix of indigenous Greenlanders with Danes, Norwegians and Icelanders who came to Greenland in the past. I think the general attitude in Greenland towards the Danes is negative, but it is really more complicated than just saying that they are seen as the bad guys.

Most Greenlanders accept the fact that they are a Nordic country and that they are related to Denmark and other Scandinavian countries. There are family ties, cultural ties, and economic ties.

But they are sceptical about Denmark because it treats them unfairly.”

Greenlanders are very warm and welcoming at heart, but first you have to gain their trust. “I would say they are more introverted than the average Scandinavian,” admits the Norwegian student. “Greenlandic culture is characterised by kindness and family spirit, they value family and the bonds that unite small communities. You have to remember that populated areas in Greenland are not connected by roads, you have to fly or use water transport to get from one village to another. And I think that brings them closer together, they look out for each other, they take care of each other.”

Danes are not against independence

“For most Danes, a Greenlander is a person with very serious social and substance abuse problems, sometimes perceived as coming from a backward culture,” writes Humanityinaction.org, quoting a popular Danish saying for a drunkard – “drunk as a Greenlander”.

Unfortunately, Greenlanders are still considered “second-class citizens” in Denmark.

According to a Yougov poll in January this year, 78% of Danes would not support the sale of Greenland to the US, while 72% believe that the decision should be made by Greenlanders themselves, suggesting that a majority of Danes would support Greenland’s independence, as many see Greenland as an unnecessary burden due to Denmark’s annual subsidies.

However, if Donald Trump were really serious about buying Greenland, it is not yet clear who would be the seller – Denmark or Greenland.

OPINIONS

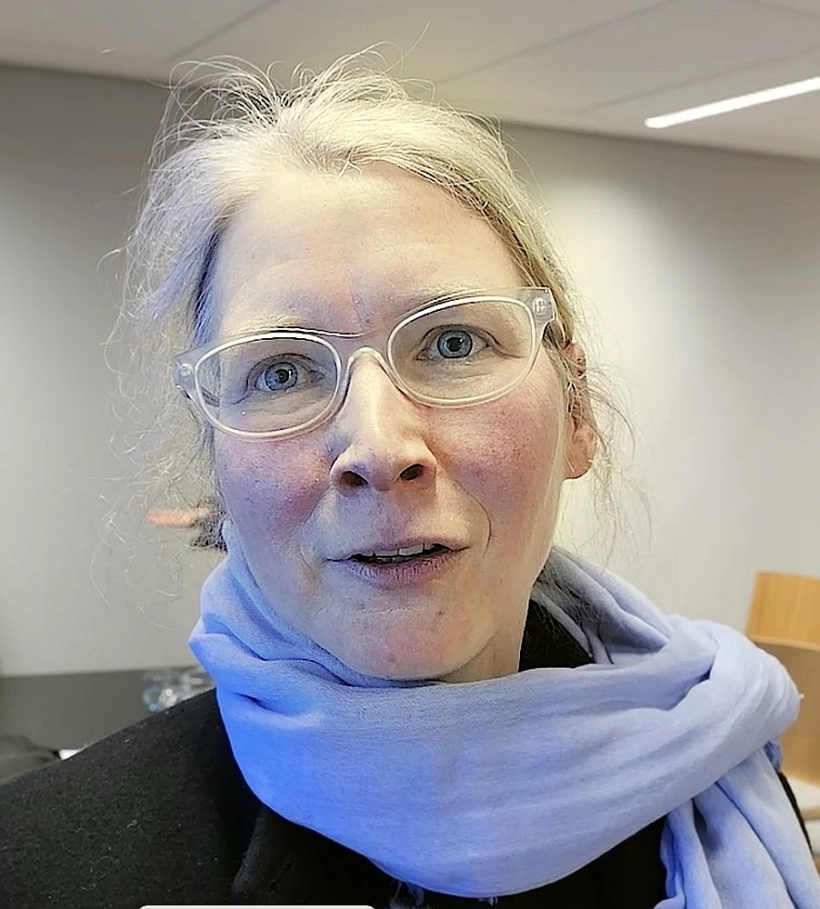

Photo: Ilze Kalve /Latvijas Avīze

Discussion warns of an end to the world order

Richard Powell, Professor of Arctic Studies at the University of Cambridge:

“In recent weeks, we have heard various statements from the new US President regarding foreign affairs. They are hard to believe, almost unbelievable, so you have to ask how much of it is true and how much is just a show-off to the world. Of course, we do not know what will happen next, however, if the Ukraine and Israel-Gaza issues are resolved as proposed [by Donald Trump], it will be an unprecedented event in post-1945 geopolitics.”

Photo: Ilze Kalve /Latvijas Avīze

Kristina Spohr, Professor of International History at the London School of Economics and Political Science:

“If indeed one member state occupies a territory belonging to another member state by force, then there will be a lot of questions, because Article 5 cannot be applied in this case, because it will happen within NATO. It will be the end of the world order we have lived in since 1945, since Helsinki and the end of the Cold War. It is surprising that, instead of working with Denmark to expand and develop existing possibilities, Donald Trump has questioned the position of Denmark, a smaller NATO member. However, Donald Trump is also questioning the position of other NATO members, for example on Ukraine!”