By László József, Népszava – MUOSZ

The Polish economy, once overlooked, has now pulled ahead of Hungary’s, while political relations between the two countries have reached a low point. Nevertheless, Marek Kłoczko, President of the Polish Chamber of Commerce, believes there remains substantial potential for economic cooperation between the two nations, as well as benefits in their EU membership.

Hungary and Poland’s political relations are currently far from ideal. But how are the economic ties between the two countries?

I’m not a political scientist, but even I can see that there is a fundamental contradiction between the political paradigms of our two countries. For us—both for the elites and for the entire nation—security is a core concern. The political doctrine currently prevailing in Russia certainly does not guarantee this for us; in fact, it deeply troubles us and compels us to take action. Regarding economic relations, however, I believe they are developing appropriately. In 2023, trade between our countries exceeded €13.5 billion, and it continues to grow steadily each year, despite a slight decline in 2023. Moreover, Polish investments in Hungary and Hungarian investments in Poland are roughly at the same level, around €1.5 billion. Of course, there is always room for improvement, and this is what we aim for at the Polish Chamber of Commerce. I am convinced that there remains significant growth potential. One key element of this potential is improving transportation conditions, including those via Slovakia. Fortunately, Polish-Hungarian relations are not determined solely by the current governments’ political agendas.

In your opinion, what is the secret behind the success of the Polish economy?

To mention just the essentials, the first factor is the entrepreneurial spirit of the Polish people.

Even during the socialist era, agriculture in Poland remained privately owned, and hundreds of thousands of small businesses operated. This was a tremendous training ground for entrepreneurship, even in challenging circumstances. Another factor is the high level of education among the population, a trait common to most former socialist countries. Additionally, there was a strong connection between the scientific and intellectual elite and the developed countries of the West, which, following the political transformation, resulted in wise decision-making. Many of these connections stemmed from family ties between Poles in Poland and their relatives in developed nations. In the early stages, numerous businesses were born from these relationships. There is also the diligence and ambition of the Polish people, coupled with a relatively large domestic market with considerable potential.

What are the main driving forces of the Polish economy today?

There are three primary drivers of growth: domestic consumption, investment, and the balance of foreign trade. In Poland, all three play a significant role, although their importance varies over time. In recent years, there has been recurring concern among economic circles about the insufficient growth of investments, prompting successive governments to be urged to create better conditions for investment.

I saw one of your statements on YouTube where you talked about the need to put an end to disorder and the many exceptions in regulations.

Sustainable economic development requires sound, sustainable, and stable regulations. In recent years, there has been a lack of predictability in the creation of regulations governing economic life in Poland, at least according to the business community. This has led to what could be called “regulatory inflation,” which has become a nightmare for entrepreneurs. In my view, this has been the main cause of the insufficient level of investments. This is not just an issue as a factor of GDP growth but is crucial for enhancing the competitiveness of the Polish economy on the international stage. The business community understands that not every regulation can be optimal for everyone, but predictable laws provide an opportunity to adapt to upcoming changes appropriately.

How did the Polish economy manage to reduce its dependence on Russian oil and gas? How significant is the loss of Russian markets, and what alternatives have been found?

Due to historical experiences, Poland has always been very sensitive to relations with its largest neighbors—Germany and Russia. Our understanding of our neighbors is deeply rooted in our historical experiences and close monitoring of the changes taking place there. The Polish elite has long recognized that the “decommunization” processes launched in Russia in the late 1980s and early 1990s were abruptly halted, and that modern Russia began to build its identity around “imperial values,” while simultaneously glorifying the era of communist crimes. This led Poland to become increasingly wary of Russia’s attempts to dominate Europe through various means, with energy resources being one of the most important tools in this struggle.

Thus, reducing dependence on Russian energy resources became a priority for the Polish government after recognizing Putin’s imperial ambitions.

This transition, of course, has come at a cost for the Polish economy, as Russia was an important economic partner. Today, trade with Russia is marginal. However, as recent years have shown, the costs of this move are still far smaller than the potential costs of inaction. Today, hydrocarbons are imported from various sources, including the USA, Saudi Arabia, Norway, Qatar, and others. We have also expanded production from our domestic gas resources.

Last year, there were many pessimistic statements regarding Europe’s economy and the EU. How justified are these concerns?

Regarding the European Union, the situation is somewhat akin to Churchill’s famous saying: “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others that have been tried.” The European Union indeed has many flaws, as its critics emphasize, but it also has many advantages, as evidenced by numerous developmental statistics and a largely satisfied population. In my view, in recent years, the elite that influences Brussels’ decisions has become too detached from reality, with the balance shifting from pragmatism towards ideology. Europe is not the only key player on the international stage, and it cannot make economic decisions independently of the activities of the US, China, or the BRICS countries, as doing so could lead to a loss of competitiveness for the European economy. The Polish Chamber of Commerce’s stance aligns completely with the views of the economic circles represented by other national chambers of commerce in EU member states: it is all about maximizing the strengths we have.

How do you see the future of the world economy? Who will be the winners and who the losers?

Perhaps it is evident that the world is experiencing a cultural revolution driven by technological transformation. Just as the Industrial Revolution in the 19th and 20th centuries “ploughed” the world map, created new leaders, and ousted the old “bandits,” the current technological revolution will also create new winners—and inevitably, there will be losers. The key lies in making the most of our strengths. There is no single “right” economic model globally. In my opinion, the important thing is that the chosen model for economic development should consider the traditions and culture of the given country.

Throughout Poland’s history, we have always been most successful when we had a strong middle class. Therefore, I believe Poland’s chance of economic success lies in reducing state control, improving the regulatory environment, and supporting the entrepreneurial attitudes of Poles.

But, as I said before, in our geopolitical situation, security issues take precedence today. And I wouldn’t dare point fingers at specific countries.

You graduated from the Budapest University of Technology and speak excellent Hungarian. How do you view Hungary now, from the perspective of many years?

It was by chance that I ended up studying in Hungary, but it was one of the best coincidences of my life. Hungary became my “second home.” However, due to my busy work schedule, I haven’t closely followed the situation in Hungary in recent years. I think that, unlike in Poland, there has been greater social differentiation here, and a wider gap between Budapest and the “provinces.” It also seems to me that, in Hungary—just as in Poland and many other countries—society has become more polarized than it was before. I believe Poland’s economic development has been more dependent on the potential of its middle class than in Hungary. Nevertheless, Hungary will always hold a special place in my heart.

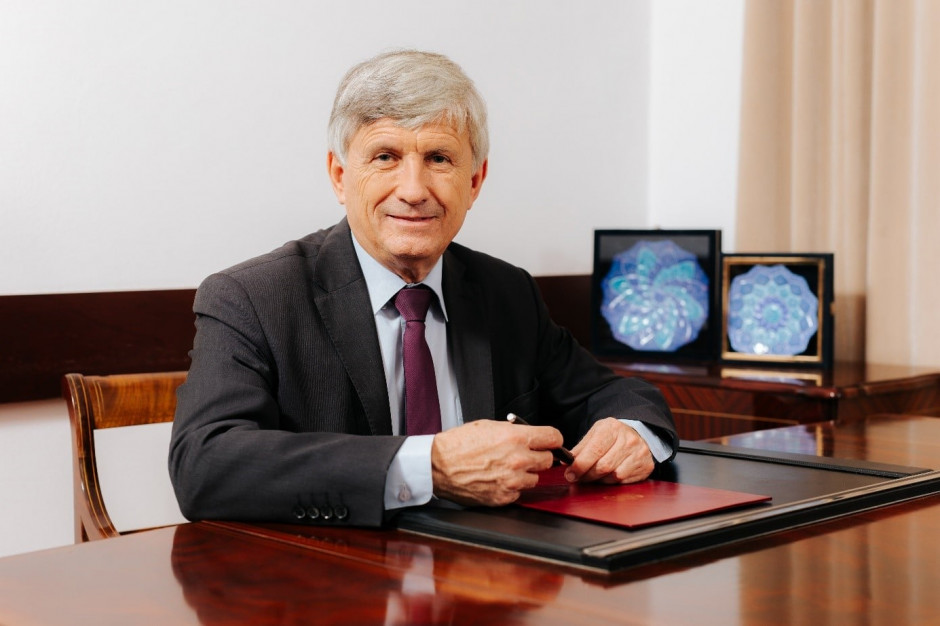

Marek Kłoczko

An engineer by training, Kłoczko graduated from the Budapest University of Technology in 1976 and later from the Faculty of Production Economics at the Warsaw School of Statistics in 1979. He is a certified translator for Hungarian. From 1987 to 1990, he served as director of Warsaw Television Factory. Between 1991 and 1993, he was a member of parliament, after which he withdrew from politics. Throughout this period, he worked continuously at the Polish Chamber of Commerce, where he has been CEO, Secretary-General, and now President. In 2015, he became Vice-President of Eurochambres, the European Economic Association.