Vásárhelyihirek.hu / Zoltán B.Szabó

It has been remarked, both by experts and laypeople alike (albeit with some exaggeration), that this year’s summer has made it clear that the Carpathian Basin, particularly the Great Hungarian Plain, is already becoming uninhabitable.

Since early spring, news of wildfires caused by drought has been coming from Southern Europe every week. In Greece, for example, a wildfire even threatened one of the outer districts of Athens. In Hungary as well, fires, both small and large, have become almost daily occurrences this year, often endangering inhabited areas. Fires are particularly frequent in the Southern Great Plain, where the drought has led to surreal situations. On September 1st, an irrigation canal near Hódmezővásárhely burned for several hundred meters, along with the reeds that lined it, even threatening nearby farms.

There is an old saying: “A person who loves flowers cannot be a bad person.” However, there is one flower that the farmers of the Great Plain do not love, though it does not make them bad people. This flower is the sea lavender, officially known as Hungarian sea lavender or Limonium gmelinii.

As its name suggests, the plant thrives in salty, dried-out soil, where almost nothing else grows. Its vivid blue hue is a decorative marker of barren, bone-dry soil and a sign of drought. This summer, and at the end of it, the Southern Great Plain has been dotted with vast blue fields, a testament to how far the drought has spread. This year, the sea lavender has claimed an even larger area than usual, as other plant species have declined due to the lack of rainfall.

Wilted corn stalks, withered sunflower heads, and cracked pastures are reminiscent of the severe drought of summer 2022. Now, the drought of 2024 has taken over as the “memory,” with an exceptionally dry stretch of months. According to statistics from the Tisza Valley Water Directorate, this year only 310 mm of precipitation has fallen, compared to the annual average of 560 mm. As early as April, the National Agricultural Chamber recommended declaring a “prolonged water shortage period.” This would mean that, during this period, exceptional use of water for irrigation is permitted without a water rights permit, following a one-time notification, and farmers do not have to pay water resource charges. The Chamber’s somewhat naive hope was that irrigation could help mitigate the effects of the drought. The intention was commendable, but the water needed for irrigation must actually reach the fields.

This brings us to the need to “dig deeper”—almost literally—into the issue. In many parts of the Great Plain, including the Southern Great Plain, the old irrigation canals surrounding arable land need to be dug out again, as they have disappeared due to neglect or have been intentionally filled in by farmers, possibly in the hope of increasing EU land-based subsidies. To be fair, this trend began back in the 1960s, when collective farms (TSZs) and state farms prioritized large-scale agriculture and neglected the canal systems.

Old maps show that even our ancestors understood the importance of building canal systems around fields with lower rainfall, as they could yield multiple benefits. The area between Szentes and Hódmezővásárhely, for instance, had an extensive canal network. Wells and water brought in from the Tisza River ensured consistently good harvests for the local farmers. According to older residents of the area, the canals not only facilitated irrigation via special irrigation boats but also allowed for the transportation of harvested crops, such as grain, corn, and hay, using boats. Archival records and old photographs testify to this practice. The irrigation period lasted from late April or early May until the end of October. Watering was necessary to ensure the even emergence and steady development of spring crops. The need remains the same today.

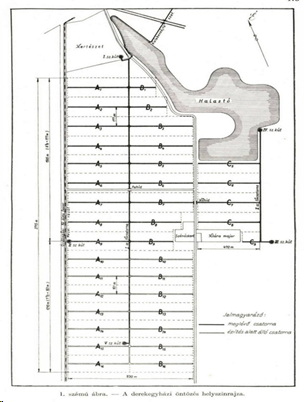

The plan for this irrigation system originated in the 1930s with Baron Manfréd Weiss, who purchased a large estate near Derekegyház. At his suggestion, the fields were divided into 200×200-meter plots with irrigation canals between them. To supply these canals, wells over 300 meters deep were drilled at several locations.

Irrigation was carried out using a boat specifically designed for this purpose. Naturally, the boat was built in Csepel, at the Weiss Manfréd Steel and Metal Works. The pumps were manufactured by MÁVAG. The boat was 34 meters long and 3.5 meters wide. The two Ganz pumps had a capacity of 4,500 liters per minute, with a reach of up to 90 meters. During World War II, the boat sank and the engines were damaged by frost, and even though the boat was restored in 1960, it could only be used for three years due to the increasingly neglected canals.

From the records, it is evident that irrigation using the boats resulted in a 30–100% increase in yields compared to non-irrigated areas. Alfalfa and sugar beets benefited the most from the irrigation. The estate also used the canal network for drainage, transporting manure, and moving crops by water. It is worth noting that the well-constructed flat-bottomed boats were easily pulled along the banks by a single person.

If we look at this area, which is not unique within the Southern Great Plain, it is evident that the changes in soil structure resulting from intensive agriculture have led to low humidity in the near-surface layers during summer heat waves. Consequently, cold fronts now pass over this area without the usual thunderstorms and rainfall. As a result, even the few remaining canals have dried up during the summer months in recent years.

As they say, the “alarm bell” has been ringing for years. Not to sound cynical, but many of the experts at various conferences and workshops on desertification—though with some notable exceptions—rarely, if ever, set foot on the Southern Great Plain’s pastures and fields, which “gasp” in the July and August heat. Both experts and laypeople have made the exaggerated observation that this summer indicated that the Carpathian Basin, and especially the Great Plain region, has already become unlivable. The process began some time ago: abandoned and dilapidated farms, once indicative of thriving agricultural activity, are now a common sight. Even wildlife (such as pheasants, deer, and hares) is suffering from the increasingly frequent droughts and the resulting lack of food and drinking water. The undergrowth of the few remaining forests has also turned bone dry.

The memory of those who were familiar with the challenges of farming on the Great Plain and were blessed with an innovative spirit is preserved today by the small-scale replica of the irrigation boat and a marble plaque erected in the center of Derekegyház.

Postscript: According to local farmers and those experienced in water management, rather than lamenting and acting as "prophets of doom," we should start digging... dig wells! As they say, there is water underground, even beneath the Gobi Desert.